Budget-Building That Delivers: Amy Omand's Secret to Numbers That Make Sense

Summary

Budgeting doesn't have to feel like choosing between intimidating spreadsheets OR crossing your fingers and hoping for the best. Amy's approach makes budgeting straightforward and human — with a process that involves the right people at the right time, creates ownership instead of resentment, and gives you something you can actually use throughout the year. (Numbers instead of just hoping for the best!)

What’s in it for you:

You're building your first organizational budget and drowning in terms like 'board-approved' vs 'forecast' vs 'funder budget' — and just need someone to explain what these actually mean

You want your team involved in budgeting without it turning into chaos or wildly unrealistic numbers — you need clear guardrails that create ownership, not resentment

You're facing cuts and need a process that doesn't destroy trust or morale — because how you do this matters as much as the numbers themselves

You're managing a team of 5 (or you're solo and wearing all the hats) and need an approach that actually scales to your reality

Helia’s Perspective

I worked briefly with Amy Omand at Revolution Foods and have loved watching from afar while she has worked across the social sector. Most recently, she’s built up her fractional CFO practice and when I reached out about contributing to the Helia Library, I was thrilled that Amy wanted to help demystify budgeting.

I've learned the hard way that a bad budget process can haunt you all year long. Early in my career, I built a budget based on the most "optimistic" scenario — everything was technically accurate, but it wasn't something we could actually make happen. I spent an entire year sitting in monthly meetings reporting how we had, yet again, failed to meet our projections. It was something we just couldn’t “come back from” — and it was unbelievably demoralizing.

That experience made me LOVE a thoughtful budgeting process where we all check each other and focus on numbers we can and will actually meet. Amy lays out a straightforward process that's great for us to see, learn from, and use as a foundation — whether you're doing this for the first time or looking to solidify what you've already built.

Amy's Story

Amy got her CPA right out of college because she loved math and the quantitative aspect of learning. As she puts it: "Business and accounting, where every debit must have an equal credit, really spoke to me as far as how to organize and tell stories about what was going on in the business or the organization."

After working in public accounting and for-profit organizations (including what she describes as "a very yummy role" at Dreyer's Ice Cream), Amy pivoted into social impact work. She had a moment where she considered becoming more programmatic, but ultimately determined that steady financial leadership was really what social impact organizations needed. “They need great people with those quantitative skills to help them think through the finances and steward the funds toward the most impact because, if there's no money, there's no mission."

For Amy, budgeting isn't just about spreadsheets — it's about creating a process that helps people understand and own the financial story of their organization.

Amy ringing in the new year on the Hanalei pier on Kauai in 2025

What this looks like in practice

-

What Amy recommends: Before anyone touches a spreadsheet, leadership needs to align on both the financial context AND the strategic priorities that should guide all budget decisions. This becomes the story of your year: where you spent money and why.

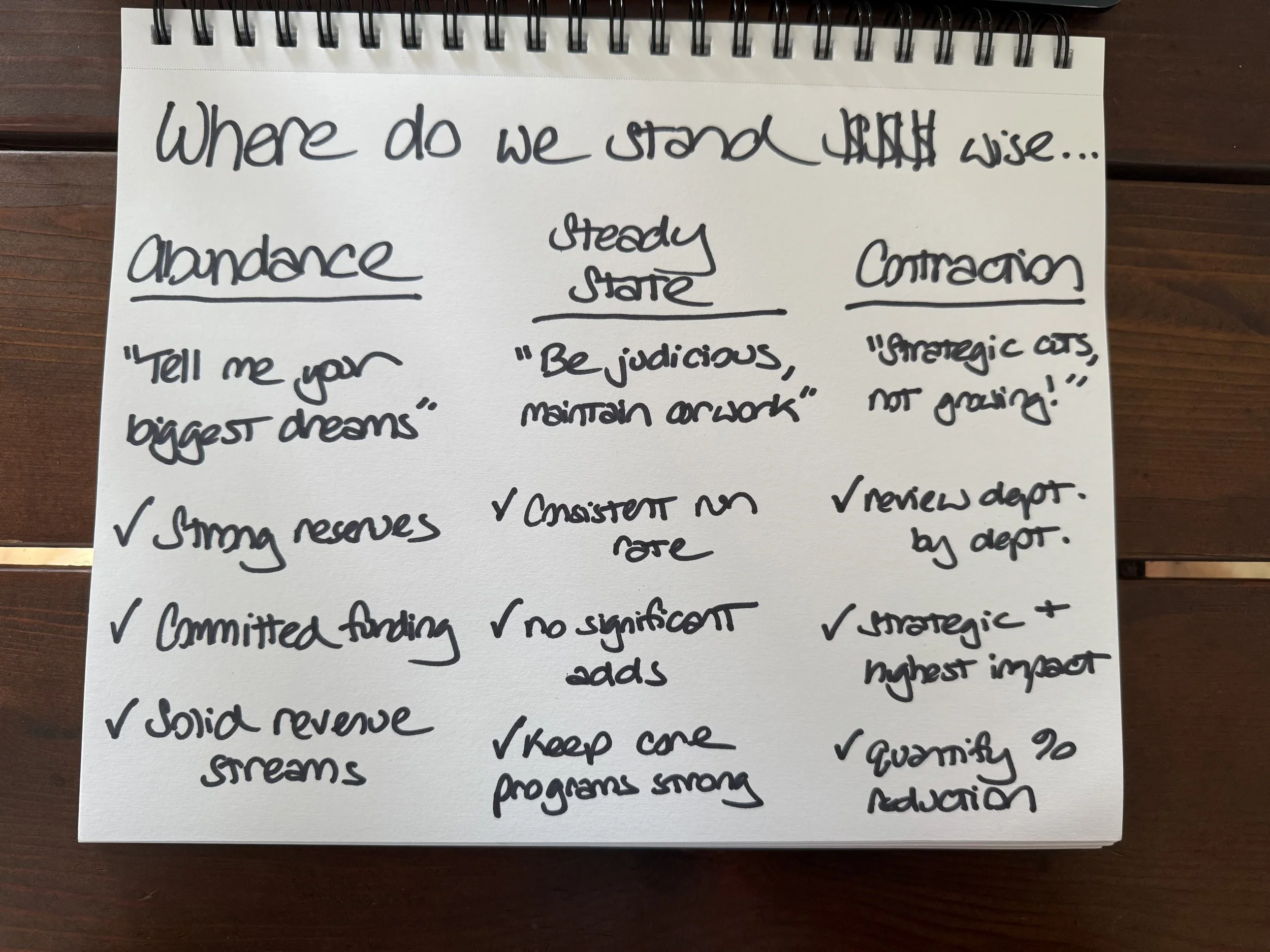

Why this matters: This determines whether you're approaching budget managers with "tell me your biggest dreams" or "we need to be really judicious." More importantly, it aligns budget decisions with what actually matters for your mission.

Financial context (Amy identifies three main scenarios):

Abundance approach: "Are you in a situation where you're confident with the amount of reserves that you have? You're heading into the year with commitments for continued funding or strong earned revenue streams? So, your approach with your budget managers can be, 'Yeah, tell me your biggest dreams and plans.'"

Steady state: "We're going to be budgeting at a continued run rate, not adding anything incremental. Let's keep up the work and the programs, but be really judicious in how we're spending."

Contraction mode: "Contraction mode is tough but it's a reality that needs to be tackled head on. Start by looking at your previous budget, then get specific: 'Program A is restricted funding so we can't touch it. Programs B and C each need to cut 15% to protect our reserves.'"

Sound familiar? Most of us are living in either steady state or contraction right now. You know you need this clarity when budget managers say things like "I had no idea we were in contraction mode!" or when your board is asking about specific line items instead of strategic questions.

What explaining contraction mode can sound like: "I want to be direct: we need to make strategic reductions this year to protect our financial health. Rather than across-the-board cuts, we're working together to identify where we can thoughtfully reduce while protecting our highest-impact work. This is hard, and we're going to get through it by being honest about constraints and strategic about choices."

Strategic priorities guidance — this is where you connect budget decisions to your bigger picture:

If expanding: What do we need to invest in now AND for the future? Which areas drive the most mission impact?

If contracting: How do we think about cuts — across the board or strategically? What work is most essential to our mission?

Connect to strategic plan: What did we commit to in our strategic plan? Where did we say we were going to invest? Amy emphasizes that good budget guidance should "align with our strategic plan AND world realities."

Give clear direction: Budget managers need to know not just the financial constraints, but the organizational values that should guide their proposals. Are you prioritizing sustainability over growth? Innovation over stability? This context shapes every line item decision.

(This sounds so obvious, but how many of us actually do this strategic alignment step before we start the numbers work?!)

-

What Amy recommends: Start budget planning about three months in advance, thinking strategically about who needs to be involved and when.

Why this matters: "This is something where you need a little bit of time planning for the plan. You're gonna plan to build your plan, and then you're gonna build the plan."

Here's what that actually looks like on your calendar:

For a December 31 year-end:

September: Clean up your chart of accounts (3 hours), draft timeline and identify budget owners (2 hours)

October: Budget managers build first drafts based on templates you provide

November: Review rounds, revisions, and strategic decisions with CEO

December: Board presentation and approval

People planning: Map out who should be involved in upcoming budgeting meetings. "You do want to have your budget owners involved in actually creating the budget for their specific programmatic areas... so that when it comes time to actually spend the funds, they are the ones that said, 'Yes, we need this contract with an IT provider. We need this communications consultant.'"

Set expectations early: "Set expectations with those budget managers about their involvement and the time it's going to take." Amy is mindful about not jamming budget work into already busy periods — like right before major conferences or during performance evaluation season.

Put it on the calendar: A budget is a must-have, not a nice-to-have. Putting it on the calendar indicates to the organization that it's a critical priority.

-

What Amy recommends: Before diving into any budget process, make sure everyone understands what type of budget you're actually building.

Why this matters: "One thing that can be overwhelming for folks is the definition of the different types of budgets and forecasts and, you know, sort of understanding what an organization needs to wrap their arms around."

Here are the four key types:

Annual board-approved budget: "This is what I consider like your northstar budget... the budget you will look at monthly if not weekly to make decisions big and small. It's important to include your budget owners (i.e., the people who make decisions about how money gets spent in their department) in building these budgets."

Funder budget: "When you're going out looking for philanthropic funding, the funder will have specific things that they want to fund and so they're going to ask you to submit a budget with your proposal. You won't give them the budget for your entire organization, just the budget you need to carry out your program."

Long-term budgets: "This is a multi-year budget – especially useful when you're thinking about things like building up your reserves or if you have the benefit of multi-year contracts."

Forecast: "Your forecast is not the same as your budget. It's the document that shows where you're tracking in real time - how are expenses playing out in real time, what revenue are you bringing in - this is always changing and adjusting. One of the things I learned years ago from another CFO friend of mine was like, 'The minute you get your budget approved by your board, it's out of date because life changes.'"

(I love this — imagine if everyone actually understood what budget they were building and why!)

NOTE: The rest of this piece will focus on advice for building your annual board-approved budget. While this type of budget does require some investment of time, Amy clarifies that the other types of budgets don't usually require a three-month process!

-

Chart of Accounts: Think of this like the backbone of your financial system. It's the master list of all the categories you use to track money coming in and going out—things like revenue, salaries, rent, travel, or program expenses. Every transaction in your books gets slotted into one of these categories, which makes it possible to build budgets, track forecasts, and report to funders.

What Amy recommends: Before anyone touches budget numbers, audit the chart of accounts to make sure it's actually serving the organization's decision-making.

Why this matters: "Even before you get into the budget building phase of things, think about your chart of accounts and how you were tracking information. Does the list of categories/accounts make sense? If you have an account that, in a single year, you've only put 30 bucks against, you don't need that account. Or, did you continuously have to download the detail of one account to parse out various transactions – you might want to consider breaking that into several accounts so the data is more easily accessible."

How to do this:

Identify your users: "Who are the users of your budgets and your financial statements?" Executives? Managers? Auditors? Your budget's primary purpose is for management to use as a tool in decision making. Its secondary purpose is auditing and tax reporting. So, your budget needs to be designed in such a way that management can use it for operational decisions AND that your tax and audit teams can easily get the information they need to do their jobs.

Audit your accounts: Look for accounts with minimal activity, overly complicated structures, or categories that don't help with actual decisions. If you're building a budget for the first time or don't have much finance experience in your organization, find an accountant to help you with this.

Ask your accounting team: "If you are large enough to have an accountant team or a bookkeeping team, see what they are really spending their time on. Are they doing these crazy allocations to sort of get numbers organized, but no business manager is actually utilizing those numbers to make any real decisions?"

Simplify ruthlessly: "All those superfluous accounts you identified in your audit? Those crazy allocations your accounting team was doing? If they aren't serving you, cut them." Amy's favorite auditors say, "Structure your chart of accounts for your decision-making, but just make sure that you can roll back up into an audited financial."

(I cannot express how obsessed I am with getting the chart of accounts right because it makes everything so much better!)

-

What Amy recommends: Involve budget managers in actually creating their budgets, but with clear context and parameters.

Why this matters: "If a budget is done top down by the CEO and the CFO, there's not nearly as much engagement and ownership of the people spending the money day-to-day."

Here's the thing: Giving people freedom without context is a recipe for disaster. Here's how to set it up for success.

Start with data: Bring the current year's budget actuals to the meetings where you're planning out next year's budget. Everyone has their actuals right there so they can say, 'Okay, well this line item was $20,000 last year.' And then you can have a conversation around increasing/decreasing/holding steady that line item.

Question what stage your work is in: This is a great moment to not just replicate the year before, but ask what's changing. Does your program need different support now that it's in year three versus year one? Is your support team able to provide what's needed at this stage? Are there things you do just because you always do them?

Know your people: Amy shared a great story about home office equipment during the pandemic — one employee asking for an $800 standing desk, another using a cardboard box to prop up their computer.

"If you've been managing these folks and you know what side of the spectrum they're on when it comes to their relationship with the budget and what they might ask for, the CEO or the finance leader needs to take that into account and perhaps push back or ask them to get creative rather than moving forward with the most expensive option."

The point isn't judging either approach — it's knowing your people well enough to give the right guidance. Some need permission to ask for what they need, others need boundaries on what's realistic.

Build in flexibility: Include space for "if I did have 10% more or an additional $50,000, this is what I would do" and prioritization ("number one is like must spend, number two is like nice to have").

-

What Amy recommends: Build in multiple rounds of review with clear expectations about the process, understanding that it might take several iterations. "Tell everyone that this is not the final budget. It obviously needs to go through several rounds of review."

Why this matters: Budgets are as complex as organizations. Even if you somehow get every line item right on the first go round, it's good to sleep on it and come back and check your work. And if you didn't get everything right on the first shot, then you've got a built-in checkpoint where you catch your mistakes.

This iterative process also prevents the nightmare scenario where you approve a budget in January and literally never look at it again — or worse, where budget managers are shocked by their year-end numbers because they had no visibility along the way.

How to do it:

Set expectations upfront: Let budget managers know this is a collaborative process that might require multiple rounds

First rollup: CEO and finance person review together: "This is what our first rollup looks like in our context. This is how much confidence we have in the revenue streams coming in."

Back to managers — as needed: This might be done after one rollup OR could require multiple rounds. "I've been in the situation where the initial cut was great... and I've also been in the opposite situation where there have been line items where, after that first roll up, the CEO wanted more information."

Work together iteratively: Instead of just directing changes, connect with budget managers each round to either help them shift their approach OR ask them to propose alternatives. "You might get it right in the first — or you might need to keep evolving and working together."

Board presentation: "I don't think I've been in one board meeting where the budget has changed. Generally, the board has lots of great strategic questions, but they are inclined to approve the budget as it's presented because they know the amount of detailed work that's gone into it."

Smores and stories around the fire at our annual family camp week, Lair of the Bear.

Takeaways

Tell the story first, then show the numbers: "Numbers alone don't work. When you actually add in the story — this is under budget because of XYZ, or let's dig in here because we're not sure why it's off — that's when people have their aha moments." This is Amy's secret sauce

If there's one thing you should do: Make sure everyone has a shared understanding of your financial context before they start budgeting. As Amy puts it: "No money, no mission" — so let people understand where you actually stand

Plan for the human element: Some people ask for "the sun, moon, and stars" while others use cardboard boxes. Know your people well enough to give the right guidance — some need permission to ask for what they need, others need boundaries on what's realistic

Common pitfalls to avoid:

Skipping the chart of accounts cleanup — you'll end up with "so many classes, so many accounts" that don't actually help with decision-making

Not engaging your accounting team early — they might be doing complicated allocations that no business manager actually uses

Building budgets that can't be used year-round — make sure your structure matches how you'll actually report and make decisions

What makes this work well:

Question your assumptions — Does your year-three program need the same investment as when you were just starting? Are there things that are "good enough" that you can maintain while focusing resources on bigger priorities?

Use it throughout the year — This isn't a one-and-done exercise. Amy recommends doing budget reviews with budget owners on a monthly or quarterly cadence

Be sure you add bullet points/commentary to your budget numbers when presenting. For example:

We are running about 20% over on travel this year - this is because we launched 3 new accounts unexpectedly and are sending the team on-site to support launch. While we are over budget, it is directly covered.

Our revenue is 10% lower than projections - while we are still working to bring it back up, we have also proactively reduced our expenses given uncertainty in the market right now.

Questions to ask yourself

Are we set up so budget managers can actually see their spending throughout the year, or are we asking them to budget blind?

What's our honest financial context right now — abundance, steady state, or contraction?

Is our chart of accounts helping or hurting our decision-making? (And be honest — when's the last time you actually looked at this?)

What type of budget are we actually building, and does everyone understand the difference?

Want to Try This?

Quick start (10 min): Download the Amy-inspired 3-Month Budget Workplan ← See the timeline, key activities, and who does what

Need the words? Budget Conversation Scripts ← Six scripts you can adapt for your toughest moments (explaining contraction mode, managing unrealistic requests, reporting variances, and more)

Deep dive (full guidance): Check out these step-by-step resources ←

Templates & Guides:

Amy also recommends the Strong Nonprofits Toolkit from the Wallace Foundation. Though it's from 2018(!), Though it's from 2018, the budgeting principles and calculations are still solid — financial fundamentals don't change that fast

Here is a sample budget memo that showcases how you can present your budget numbers to your board of directors for approval, and include the context

If you are a person that likes to tinker with tools, and have some $$ to spend on a platform that could replace G-Sheets/Excel, we’ve heard good things about Martus and Budgyt – two platforms described as cost-effective and nonprofit-friendly by other trusted finance folks (Caveat: Amy has always defaulted to the flexibility and customization of Excel!)

Recommended Reads:

Managing to Change the World by Allison Green and Jerry Hauser

Connections

Need fractional CFO support? Reach out to Amy* at amy@7seatconsulting.com with subject line "Helia Connect"

Need to rethink your outsourced bookkeeping? Amy recommends two firms – Scrubbed (https://scrubbed.net/) and Jitasa (https://www.jitasagroup.com/)

You'll know this process is working when: Budget managers feel ownership over their numbers (versus uncertainty), your board asks strategic questions (versus line-item questions), and you're actually using your budget for monthly decisions instead of forgetting about it after January.

*Helia Collective Member

About the Contributor

After getting her CPA right out of college, Amy discovered her superpower: making numbers tell stories that help organizations make better decisions. She spent years working everywhere from Dreyer's Ice Cream (which she describes as "very yummy") to social impact organizations before starting her own fractional CFO practice. Her secret is understanding that behind every budget line item is a human who needs context, ownership, and clear expectations to do their best work.

This article comes from a coffee chat with Amy in September 2025. These conversations form the heart of the Helia Library – because I've learned the most from doing and from talking with other doers willing to share their wisdom. We don't need to start from blank pages or do everything alone.

As always, take what's helpful, leave what's not, and make it your own.

Article & Resource Tags